Data Criticality

A response to Caroline Sinders’ Rethinking AI through Feminism and Daniel Cardoso Llach’s Sculpting Spaces of Possibility

Sinders and Llach both situate themselves in a context of data criticality - a conversation that seems to have started in the last decade (in my experience). That is: our applications of technology increasingly leverage machine learning, which relies on data collection, cleaning, and labelling - and every step of the process is vulnerable to social forces including bias, power dynamics, and control. This critical reflection challenges the assumption our society has made that computational practices are inherently logical and correct - rather than the (in retrospect) obvious conclusion that systems constructed by humans are susceptible to the same flaws and inequalities that affect our society. The term "sociotechnical" (which I had not heard prior to this program!) feels especially apt now, capturing how inseparable the social is from the technological.

Sinders draws on a background I have grown familiar with, including The Toaster Project, The Critical Engineering Manifesto, and the maker movement. I would also bring in the perspectives of Donna Haraway, Robin Wall Kimmerer, and other environmental feminists. (In a way, it seems "feminist" has become a catch-all for critical, reflective questioning - a thoroughness in making while knowing where things come from and what forces act on them.) There's an energy I get from this context - that as designers and engineers and citizens, we are empowered to make and shape design products to serve interests beyond those of capitalist and corporate structures. This act results in a one-off art project or story to demonstrate what's possible, an intense learning and discovery process for the artist themselves, and maybe a model for how impactful work using computation can still happen at a small scale (added up). This possibility is what draws me to citizen science, and the framing of my thesis overall. If citizens can sense and collect "valuable" data by paying better attention to their surrounding ecology, they both gain the individual journey of learning and meaning-making and they contribute to a shared dataset on the health of their area with capitalist (?) and social definitions of value.

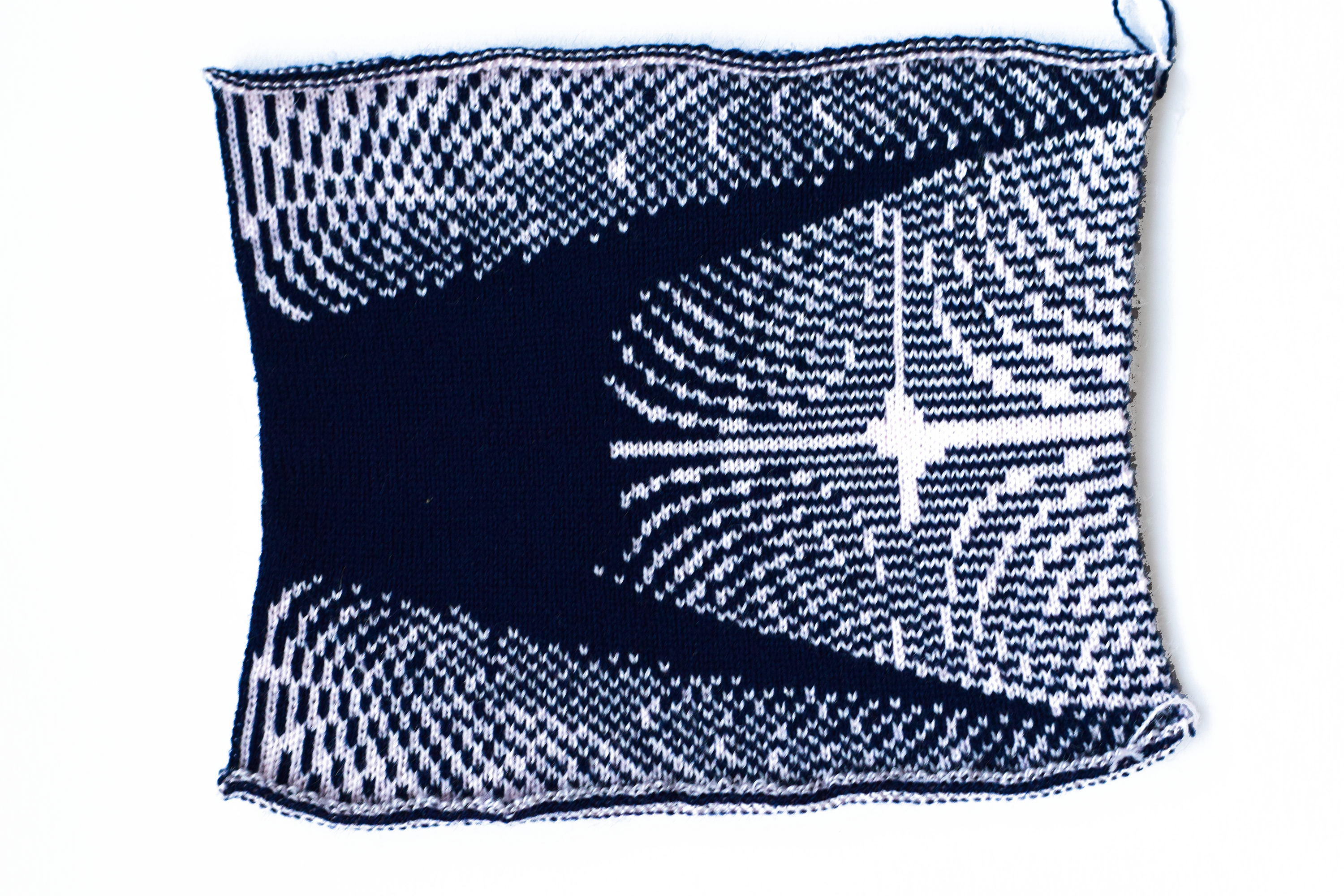

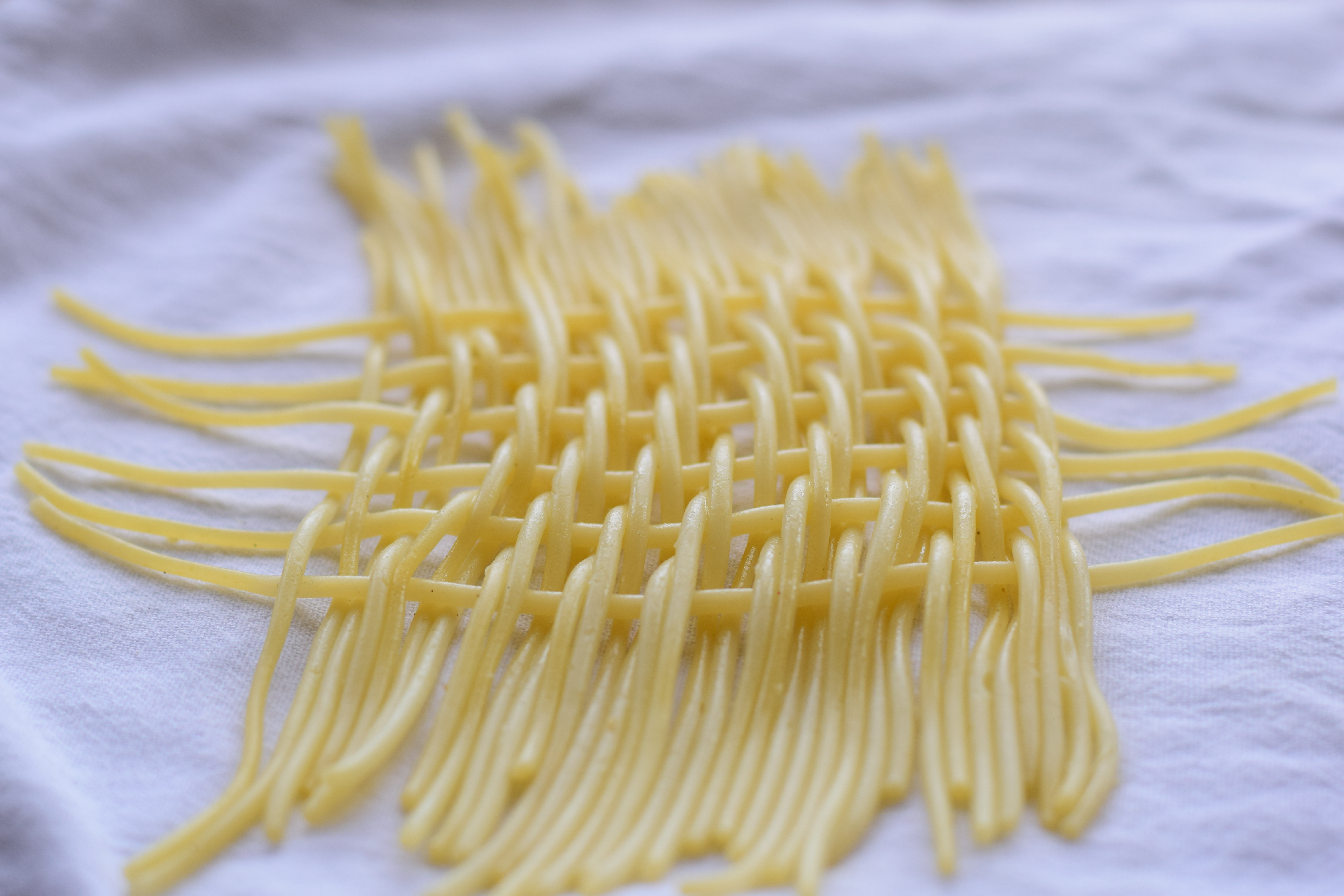

Llach draws on examples from the early stages of computation for generative, creative purposes and from more recent projects coming from the CODE Lab - the most salient question to me being: how much of a "hand" do we have in our data? In the small-scale or more (human) labor-intensive examples (Wekinator, Stiny & Gips, Hiller & Isaacson), humans are working closely with each piece of data, touching each one, turning it over in their hands to feel the flaws and sense the patterns. I notice here that I'm attracted to words that are typically used to talk about craft - because we are talking about the craft of data, time spent almost intentionally on laborious tasks, so the craftsperson finds themselves attuned to and carefully shaping their material.

With Sinders' article in mind, I wonder if this is an inescapable requirement for a truly "Feminist Data Set." To use data and machine learning critically, do we need to make sure a human is touching every piece of data? How is this possible when we get to big data sets? Maybe this is where I am missing a point - is the ideal to take a thorough, critical approach even in production-level and corporate applications of machine learning? I would think they're almost mutually exclusive, as there always seems to be a tradeoff: where we approach scaled production, efficiency, and abstraction - we add to the distance between producer and consumer, we lose empathy and attention to detail. When more becomes technologically possible, we cannot pay as much attention to what goes into it. So then, what is the goal of a project like Feminist Data Set (or The Toaster Project)? I am always impatient for greater impact, but I'd think the goals are more humble: to prove it's possible with time and labor, to inspire further work, and potentially to develop an approach that can eventually translate to production-scale applications.

Ways of Learning: Froebel Gifts

Friedrich Froebel was, among other things, a German educator who researched childhood development and learning in the early 1800s. We can thank him for building upon the ideas of previous education theorists1 to lead us to many of the fundamental ideas behind modern education (and architecture!), including kindergarten, learning through play, and the Froebel Gifts.

Froebel's Gifts were a set of educational toys intended to be "gifted" to children in a specific progression to develop their understanding of the world and their own innate "gifts".2 If you haven't heard of them before, you've more likely heard of those they influenced and inspired throughout life: the likes of Frank Lloyd Wright, Piet Mondrian, Le Corbusier, Buckminster Fuller, and Wassily Kandinsky.3

The gifts look like pared down, plastic-free versions of the toys I'm familiar with from my own childhood (likely because they influenced them!) They help children learn cumulative and increasingly complex lessons through basic geometries, soft and hard materials, colorful shapes, and building blocks. The first gift is a set of soft, colorful yarn balls that embody concepts of being/not being, color, and motion: a gentle introduction to the world that the child has newly joined.

![]() 2

2

Froebel described all the subsequent gifts as enabling play in Life, Knowledge, and Beauty. When the child builds houses, towers, and trains, the gifts become imaginitive tools for representing things from the child's life. Through other forms of play, they are facilitators for learning geometry, counting, vocabulary, and concepts of abstraction. As the child discovers how the gifts can be arranged and transformed, they become materials for creating patterns, symmetry, proportions, and iterative designs.2

Mathematics, design, and art are allowed to blur together and coexist in these minimal toys - it seems almost as a direct product of Froebel's own life experiences. His path was winding and interdisciplinary, and his careers and aspirations included forestry apprentice, architect, teacher, and crystallographer.

It seems the latter job was the one that crystalized (sorry, I couldn’t help myself) Froebel's philosophy on learning and creativity. In studying crystals, Froebel saw how nature encompassed all disciplines: science, art, mathematics, social science, education. In his own words:

Froebel's Gifts were a set of educational toys intended to be "gifted" to children in a specific progression to develop their understanding of the world and their own innate "gifts".2 If you haven't heard of them before, you've more likely heard of those they influenced and inspired throughout life: the likes of Frank Lloyd Wright, Piet Mondrian, Le Corbusier, Buckminster Fuller, and Wassily Kandinsky.3

The gifts look like pared down, plastic-free versions of the toys I'm familiar with from my own childhood (likely because they influenced them!) They help children learn cumulative and increasingly complex lessons through basic geometries, soft and hard materials, colorful shapes, and building blocks. The first gift is a set of soft, colorful yarn balls that embody concepts of being/not being, color, and motion: a gentle introduction to the world that the child has newly joined.

2

2Froebel described all the subsequent gifts as enabling play in Life, Knowledge, and Beauty. When the child builds houses, towers, and trains, the gifts become imaginitive tools for representing things from the child's life. Through other forms of play, they are facilitators for learning geometry, counting, vocabulary, and concepts of abstraction. As the child discovers how the gifts can be arranged and transformed, they become materials for creating patterns, symmetry, proportions, and iterative designs.2

Mathematics, design, and art are allowed to blur together and coexist in these minimal toys - it seems almost as a direct product of Froebel's own life experiences. His path was winding and interdisciplinary, and his careers and aspirations included forestry apprentice, architect, teacher, and crystallographer.

It seems the latter job was the one that crystalized (sorry, I couldn’t help myself) Froebel's philosophy on learning and creativity. In studying crystals, Froebel saw how nature encompassed all disciplines: science, art, mathematics, social science, education. In his own words:

Geology and crystallography not only opened up for me a higher circle of knowledge and insight, but also showed me a higher goal for my inquiry, my speculation, and my endeavour. Nature and man now seemed to me mutually to explain each other, through all their numberless various stages of development.4

[1] Avoiding the hero narrative here. He didn't come up with it all from nothing!

[2] https://www.froebelgifts.com/gifts.htm

[3] https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/froebels-gifts/

[4] Autobiography of Friedrich Froebel, cited by Bart Kahr in "Crystal Engineering in Kindergarten,” Crystal Growth & Design 2004, https://doi.org/10.1021/cg034152s

[2] https://www.froebelgifts.com/gifts.htm

[3] https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/froebels-gifts/

[4] Autobiography of Friedrich Froebel, cited by Bart Kahr in "Crystal Engineering in Kindergarten,” Crystal Growth & Design 2004, https://doi.org/10.1021/cg034152s